The Only time I fundraise

or the story of the heroes who saved Little Khang

In 2016, I was working at a research lab near National University Hospital (NUH) and working on Give.Asia’s website in my spare time. One afternoon in October, I saw a spike in traffic to a campaign on Give.Asia. The campaign was for “Little Khang”, a 20-month baby from Vietnam seeking treatment for HyperIgM syndrome, a disease affecting his immune system.

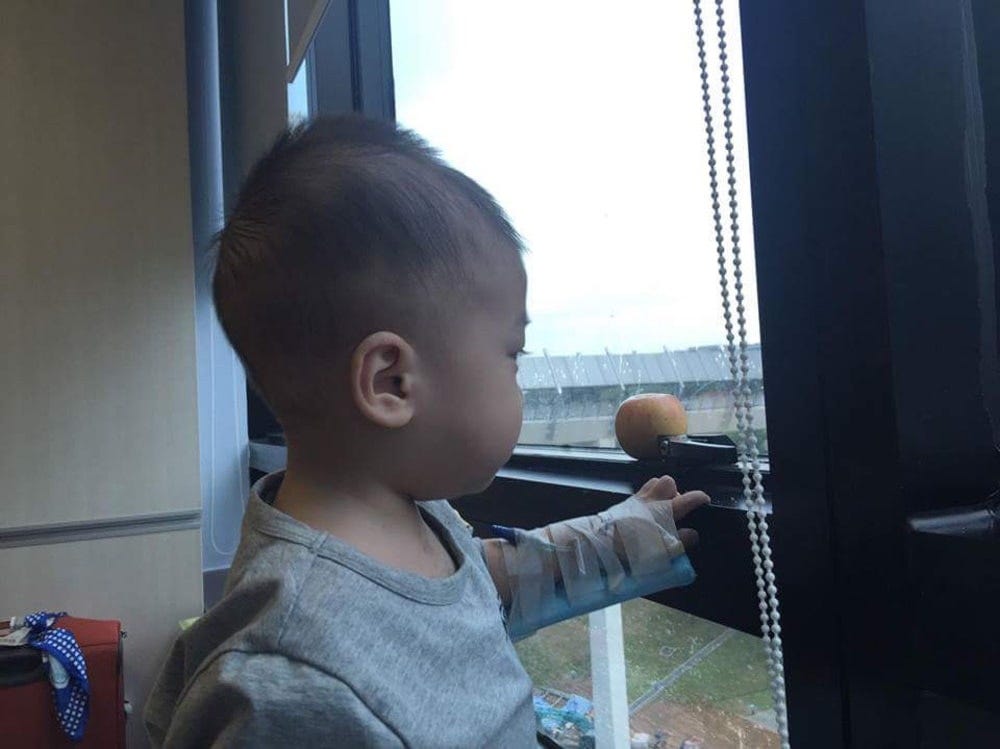

What caught my attention the most on the campaign page was the photo of baby Khang staring out of the hospital windows while it was raining outside. Even now when I looked at that photo, I still feel a tug in my heart because it reminds me of how I felt when I first came to Singapore to study. The heavy rains here often evoke memories of my hometown. Peering out of the window on a rainy day, the glamour and modern appearance of Singapore become blurred and blended together, transforming the landscape to resemble the view from the windows of my childhood home. When I saw Little Khang’s photo, I couldn’t help but wonder if he, too, was missing his home.

Are you thinking of your home, little one?

I got Khang’s mother’s Facebook account from my team. I messaged her to ask if we can help with anything and she invited me to drop by the hospital. Greeting me was a small, thin lady, wearing glasses with a tired but friendly smile. She looked frail and somehow made me feel as if she wants to be invisible in the hospital ward. I got that impression from many mothers in the children’s ward, as though wishing to blend into the hospital surroundings and hide away from some unseeable danger lurking over their children.

The nurses were very kind and helped me get into light protective gear to go see Khang. We went into little Khang’s sterile room where his dad was playing with him across the crib bed’s fences. Then Khang’s mom recounted his story to me. She told us about her friend in Singapore who suggested they come over, housed them, and helped with the initial hospital deposits. She told us about their kind doctor at NUH who helped write up the campaign on Give.Asia.

She also told me more details about their story. In our native tongue, she could recount the details more vividly. She told me Khang’s nickname at home is Khoai, which translates to “Sweet Potato”. She told me the countless times she carried little Khang in her arms when his fevers spiked. She recounted the names of all the hospitals in Vietnam they have come to find the right diagnosis. She told me the times when her little baby need to have a giant needle poked through his back to collect spinal fluid samples. She was calm. It might have been her hundredth time reliving these memories.

Khang’s mother also told me about Khang’s elder sister. She had to leave her daughter in Vietnam with her parents. This was when I heard the pain in her voice. The pain of not being able to take care of her daughter, who’s not much older than Khang and still at the age when she needed her parents the most.

Khang’s mother asked what she could do to raise enough funds for him. We were not sure, but we told her to try giving donors updates. We hope that if there is regular news, some donors would spread the word within their networks and others would be motivated to contribute. It turned out that there was a dilemma: the next important update of Khang’s treatment would be the bone marrow transplant, but he could not have the required surgery until the fundraising campaign raises enough funds. During this waiting period, Khang had to remain in inpatient care, ensuring his condition was stable and ready for surgery. No news this time means good news (he did catch a few infections and had to be operated on to clear fungal infections that got into his bones).

I spent that night putting together a video about Little Khang. I didn’t know if it would help, but I thought perhaps if I can try my best to pick the right photos, the right words, the right music, more people may resonate with Khang’s story just a little bit and make a donation.

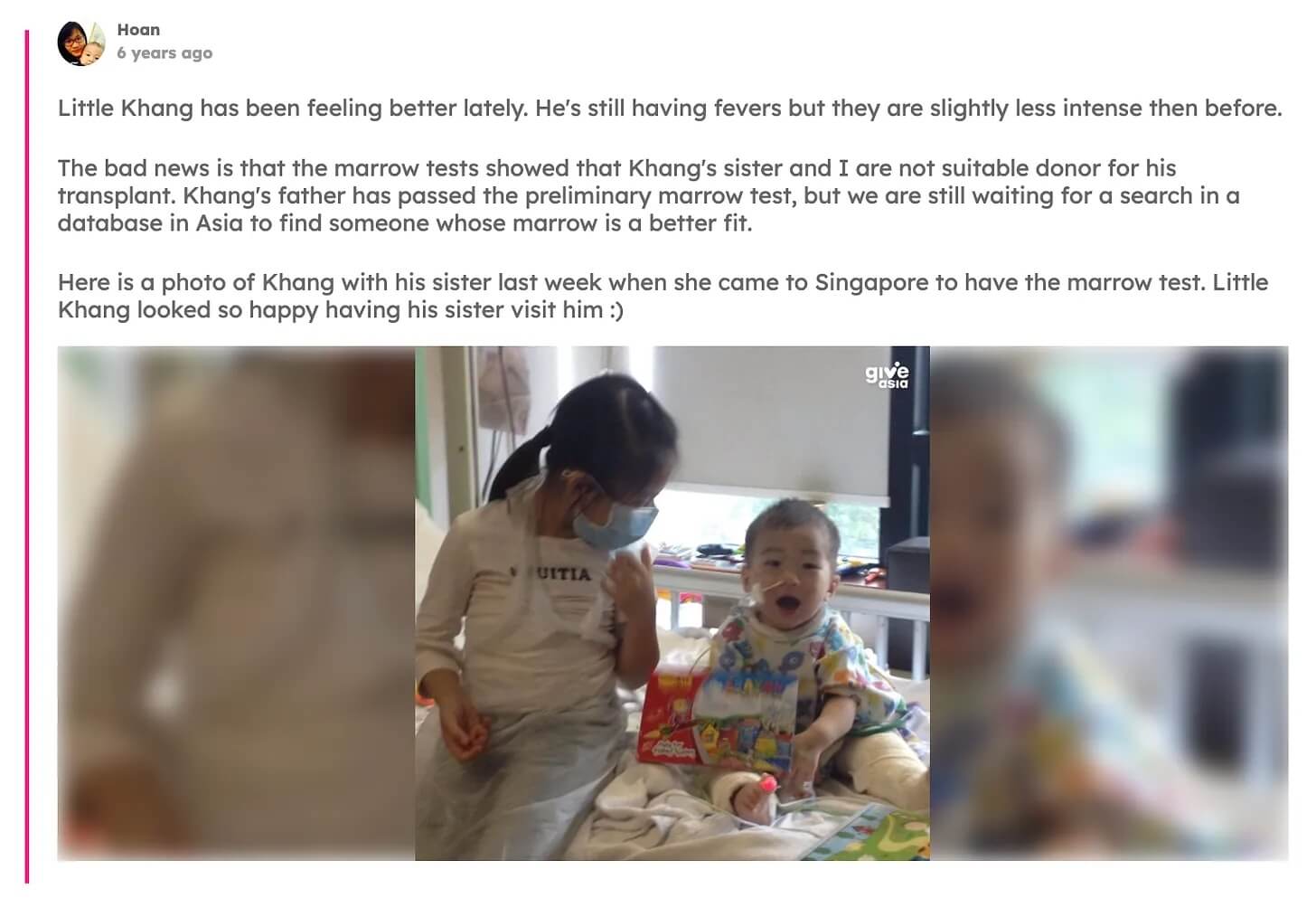

Khang’s mother messaged me every now and then about Khang’s status. I assisted her in translating these messages into updates. Some include images of hospital bills that require concealing certain details before posting. On occasion, there is uplifting news, like when his dear sister visited for marrow testing to determine if she could be a suitable match.

Sometimes, they are anxious messages about the bills for the prolonged stay that could eat into the funds reserved for the surgery. Other times, they are just a few lines updating me about new fevers, or Khang’s crying because he has to fast for procedures. Sometimes, Khang’s mother just said she feels so hopeless. Sometimes I don’t want to ask for more updates because it may just pain her more.

Almost miraculously, little Khang’s campaign managed to gather enough to meet the original goal of SGD200,000. However, by that time, the inpatient hospitalization bill had escalated to SGD169,000. When the campaign was created, Khang’s mother could not have foreseen this or known what the eventual inpatient bill would amount to. Then there’s another problem. No one in Khang’s family was a perfect match for his bone marrow. His doctors estimated the success rate of the transplant to be 50%. What if he needs another attempt? Should we raise the campaign’s target in anticipation of that statistically more likely scenario?

In the end, we informed our donors about the inpatient bill and raised the campaign’s target to cover the originally intended transplant as well as a portion of the inpatient bills.

And another miracle occurred. Our givers responded once again, and we raised enough funds. Khang’s doctors proceeded with the surgery, and it was a success. This took place in January 2017, three months after I first met Khang.

There are many things I learned from Little Khang’s campaign:

-

Extra help for campaign fundraisers: Khang’s mother received help from his doctor to set up the campaign. Fundraisers are often family members of those in need, usually overwhelmed and distressed. It could be too much to expect them to think strategically or rationally at all times. We introduced a feature allowing multiple co-fundraisers for a campaign. This enables other family members or friends to contribute towards the campaign’s success. We now also have case managers on Give.Asia to support and guide fundraisers in their campaigns.

-

Safety of givers’ donations: we were unprepared to handle large sums of donations to personal campaigns at the time. To ensure donations reach the intended recipients, such as hospital patients like Khang, we now directly transfer 100% of the donations to the hospitals based on their official billing.

-

More sustainable strategy to reach donors: to expand donor outreach on social media for little Khang, we reached out to our friends working at Facebook for free ad credits to boost his Facebook posts. While ads did provide additional exposure and attracted more donors, relying solely on donated ad credits proved unsustainable. We’ve since established a dedicated marketing team to optimize our advertisement strategies for campaigns. We also introduced the concept of “ads boosting”, where a portion of the received donations is used to generate more awareness on social media. The funds allocated for boosting are directed to payment for social marketing companies like Meta and Google. As social marketing aids in reaching more users and can result in increased donations, campaigns often experience a net positive surge in donations, sometimes multiple times more than the initial funds assigned for boosting.

The lessons derived from Little Khang’s campaign, along with numerous campaigns from our early days of assisting medical fundraising, have profoundly influenced the core offerings of Give.Asia. We remain committed to continued learning, staying attuned to new generations of givers, new technologies, and new social trends. Perhaps the most enduring lesson from my encounter with Little Khang’s campaign is that fundraising and giving differ markedly from our daily experiences. The more we facilitate a connection between everyday givers and the experiences of beneficiaries and fundraisers, the more empathy and kindness will pour through.

Back in 2016, I didn’t fully comprehend the struggles faced by little Khang’s family. Looking back at the campaign’s photos and my messages with Khang’s mother, I can now vividly recall the image of my wife embracing our older son in a hospital bed when he was two. The memories of wandering the hospital hallways with my one-year-old second child, who fell asleep while connected to an antibiotic pump, flood back. I think I can feel their pains more than I used to. But I also think now I can more fully appreciate the overwhelming joy of seeing their kid recover.

This is a tale of happiness. This is a narrative of heroes. The hero is Khang, the little boy who clung to his smile and innocence despite enduring immense pain and suffering. The hero is Khang’s mother, Hoan, a regular mother whose extraordinary determination made the impossible possible. The hero is Khang’s father whose bone marrow gave his son another life. The hero is Khang’s sister who gave up precious time with her parents for his little brother. I met her when she came to NUH for the bone marrow test. She inspired me to register for BMDP’s registry that same day.

The heroes are Little Khang’s doctor and nurses, who not only provided care throughout his treatment but also assisted his family in crafting the fundraising campaign. The heroes are the journalists who kindly responded to our appeals for help and featured Khang’s story. The heroes are the 2,174 givers who donated and shared Khang’s story. Their amazing kindness helped a little boy to see his home again.

I was fortunate to witness and document this kindness story. During those dark days, I once asked little Khang’s mother what she wanted to share with her givers. The translation was the first update I helped send to all the campaign’s givers. Though my translation was terrible I still recall how the original poem touched my heart many years ago. I’m glad her dream came true.

Today, when Little Khang saw a bird flying by the window, he asked me “Little bird, where are you going? Are you going to school?”

I remember when we were at home, Little Khang asked Grandpa’s chicken “ Little chicken, have you eaten?”

I remember he asked the fish swimming in the pond “Little fish, where are you swimming to?”

I remember he asked the dog sitting under our table “Little dog, are you sleeping?”

Little Khang’s world now is only the hospital. His world now only has Mommy and Daddy, our doctors and nurses.

I dream of the day my Little Khang can be free of tubes and needles.

I dream of the day my baby can be back to our little house filled with sunshine.

I dream of watching my baby wandering in our little garden, playing with Grandpa’s plants.

I dream of watching him playing with his sister, annoying her while she’s studying.

I dream of walking my Little Khang outside to the playground with Daddy.

I dream of seeing my baby growing up fit and healthy. I dream of watching him playing soccer, flying kites, doing all the things I did when I was a child.

I dream of Little Khang having a normal childhood like other kids, healthy, happy and carefree.

I pray everyday for my dream to come true.

Thank you so much for all your kindness.

Mommy

Khang and his sister, 2023. All is well.